‘We’re One of the Very Few Winners in a World Full of Losers’: How English Wine Is Benefiting From Climate Change

Link to original article

Inside the rare industry that's fortunate to see temperatures inch up.

Standing on an elevated, panoramic terrace of a winery restaurant, I look out over rows of vines stretching straight and even to the foot of the steep chalk ridge that extends as far as I can see to either side along the valley. It is November, and the leaves are mottling yellow and brown and falling away to compost around the rootstocks. Behind me, the hundreds of tons of grapes produced by these vines over the summer have finished their first fermentation in the winery’s vast stainless-steel tanks. These base wines will soon be tasted and blended by the winemakers before being aged in the bottle using the traditional méthode champe-noise to acquire their flavor and fizz. The quality of the fruit produced during this past long, warm summer suggests that the vintage might be one of the best ever. We’ll know in three years.

But I’m not in Champagne. On the other side of that long, high ridge lies the English Channel, and I’d need to cross it and travel another 200 miles southeast through France to reach the region most renowned for sparkling wine.

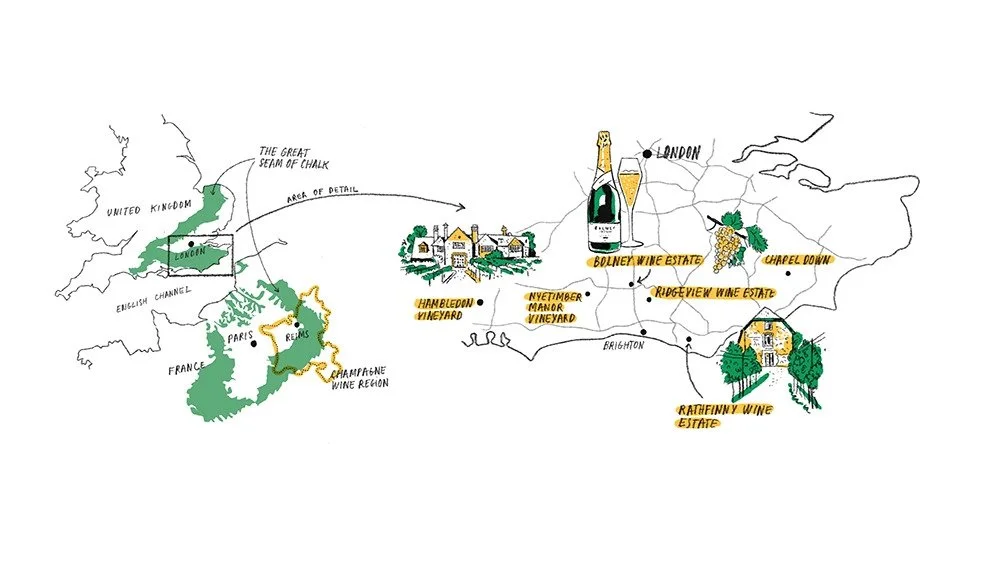

Instead, I’m at the Rathfinny wine estate near Alfriston at the heart of English sparkling-wine country, centered in the southern counties of Sussex, Kent and Hampshire. It is nearing winter in northern Europe, yet it’s unusually warm here, and I can wander through Rathfinny’s vines comfortably in just a sweater. But perhaps we need to rethink what constitutes “unusual” weather. Making great wine is a complicated and delicate balance of skill, soil and, most importantly, sunshine, and the one-degree Celsius (roughly two degrees Fahrenheit) increase in average global temperatures is having a dramatic effect on winemakers around the world. In just 40 years, the ideal climatic conditions that produced the Champagne that countless revelers have sipped to ring in the New Year and toast celebrations have shifted those same 200 miles northwest—here, to southern England. There are other reasons why the area is now one of the world’s fastest growing and most exciting wine regions, but the most significant is climate change.

An aerial view of Rathfinny, with Flint Barns, offering a namesake restaurant and overnight accommodations, in the foreground.

Tom Parker

The impact on the wine industry will be huge. Rathfinny and the other English sparkling-wine makers are winning international awards, attracting deep-pocketed investors and booming in output. Just under 10 million bottles of English wine were sold last year (for context, 322 million bottles of Champagne were sold in 2021), and the industry aims to quadruple annual production within two decades. Around 70 percent of production is sparkling, because it’s perfectly suited to the conditions and is more profitable. But the country’s still wines are improving quickly, too, with the warmer temperatures resulting in more reliable, fuller-bodied reds. Nearly 900 vineyards and close to 200 wineries are now operating in England, with over 10,000 acres of land under vine, an increase of 70 percent over just five years.

Millions more vines are being planted, some of them by the great Champagne houses themselves. Taittinger and Pommery have established vineyards in England, and other venerable names are actively looking for land or trying to buy existing wineries. Overseas investments aren’t new concepts for them, and their involvement is a result of both their newfound respect for English winemaking and their desire to maintain their market share in the UK, Champagne’s largest export market, as more English consumers support the home team.

While English grapes are enjoying just the right degree of warmth, the Champagne region’s fruit is becoming uncomfortably hot. Winemakers there are having to work harder to maintain quality and character amid ever more scorching summers and earlier harvests. Few are bold enough to predict the demise of Champagne as we know it. But should climate change permanently alter the nature of the region’s signature product, or even prevent sparkling wine from being produced there entirely, a cooler English outpost will look like a prescient investment.

The buzz around English sparkling wine might be new, but winemaking here is not. Evidence suggests that the Romans planted vines north of London, and the Domesday Book of 1086 records 42 vineyards. In 1662, the English physician and scientist Christopher Merret presented a paper to the Royal Society noting how the English were adding sugar to imported still wine in the bottle to induce a secondary fermentation—and thus, fizz. This is the same méthode champenoise (or traditional method, as it’s known when employed outside the Champagne region) that the French monk Dom Pierre Pérignon popularized in Champagne 35 years later.

Vineyard map illustration

Supplied

The English might have gotten to bubbly first, but for centuries their climate meant they couldn’t do much about it. Europe’s Little Ice Age from the mid-1300s to the mid-1800s made it too cold to produce wine at scale. Commercial viticulture is a relatively recent phenomenon in England, with more than half of the country’s current vines being planted in the 2010s. But there are already some second-generation winemakers for whom English wine has been their entire life’s work and who have witnessed the explosion in the quantity and quality of English wines, as well as the impact of climate change.

The Bolney Wine Estate, located a few miles north of the coast, in the heart of Sussex, was among the first commercial vineyards, established half a century ago by Janet and Rodney Pratt. Their daughter, Sam Linter, is now the managing director. “I remember being very tiny and helping at harvest,” she says. “There wasn’t much money in those days, so we’d get friends and family to help. Some of them weren’t the youngest, shall we say, and couldn’t bend down to pick the lowest bunches, so that was my job.

We only had two acres at the start, and we’d push the grapes between the vines in an old pram Mum found.”

“They were pioneers,” Linter says of her parents. “Dad had worked on a vineyard in Germany and was convinced we could do the same here. Everyone told them they were bonkers, but they had the vision. I don’t think they thought it would take 50 years to get there, though.”

Just eight miles away, at Ridgeview, near the charming village of Ditchling, Simon Roberts is also a second-generation winemaker, his parents having planted their first vines in 1995 on what was then a largely derelict farm. Simon stayed here for a summer to help with the planting before starting a planned undergraduate degree in yacht design. But he stuck with wine and now runs the business as winemaker alongside his sister, Tamara, the CEO.

Tamara and Simon Roberts at Ridgeview, founded by their parents in the ’90s

Tom Parker

“When we first started farming this land, winter was November through to March,” he says. “But winter is now just January and maybe a bit into February, and then spring starts. We have a much longer growing season than Champagne now, and what’s really key is not the change in peak temperatures but the mean temperature over the whole year.

“Even in the last five years, it’s been consistently drier and warmer in the summer,” he continues. “Those changes are dramatic, but they’re accelerating so much quicker in mainland Europe than they are here because of the maritime effect of being on an island.”

None of these winemakers take any pleasure in global warming. They’re simply doing what farmers have always done: growing the right crop for their conditions. “Climate change is devastating ecosystems, it’s devastating economies, it’s devastating communities,” says Greg Dunn, an Australian academic who leads the wine department at Plumpton College, located close to both Bolney and Ridgeview. “We’re one of the very few winners in a world full of losers.”

Dunn’s lecture halls and laboratories mix kids in their late teens with older students who’ve already made fortunes elsewhere, which they’re now plowing into local vineyards. Once trained, they’re all mingling with exciting young foreign talent, such as Bolney’s Cara Lee Dely, a South African, drawn by the improving conditions and the chance to run a winery far earlier in their careers than they could in more established wine regions. Together they’re creating a cadre of brilliant British-based winemakers, and that expertise is having as much impact on the quality of English wine as the changing climate is.

Bolney winemaker Cara Lee Dely

Tom Parker

“The warmer conditions mean there’s more complexity in the wines now,” says Roberts. “But the wines have changed because we’ve gotten better as winemakers, too. We are such a young industry, and it’s only in the [past] five years that I feel that I’m doing a pretty good job.”

Others might contend that Ridgeview has been good for much longer. In the so-called Judgment of Paris, in 1976, the judges—nine French wine experts—rated Californian wines higher than their Bordeaux and Burgundian rivals in a blind tasting, finally proving that new-world wines could at least match those of the old. The closest that English sparkling wine has come to its own Judgment of Paris moment was in 2010, when Ridgeview’s 2006 Blanc de Blancs won the Decanter International Trophy for Sparkling Wine—the first time an English wine had won a major international award against Champagnes and not just other non-Champagne sparkling wines.

Whether as a result of climate change or the skill of the winemakers, British examples have only improved since then, and other top English sparkling-wine houses, including Nye-timber, Chapel Down, Hambledon and Rathfinny, have joined Ridgeview and Bolney in acquiring international reputations. English sparkling wine still has the lightness, crispness and acidity typical of cool-climate wines—what Simon Thorpe, the British master of wine who heads the industry body Wines of Great Britain, describes as a “refined, precise tension.” But the greater complexity that Roberts describes comes largely from the longer, warmer summers, which allow more “hang time” for the fruit on the vine. Those extra days in more intense heat impart greater phenolic ripeness in the grape—essentially, the development of flavor as well as sugar, which tends to happen earlier. More sunshine also means more sugar, but cooler nights help English wines maintain their acidity levels and thus their distinctive freshness. That’s balanced by more fruit flavor now, yielding increasingly rounded, sophisticated wines, more comparable to Champagne and more appealing to a worldwide audience.

Roasted Jerusalem artichoke and kale salad at the vineyard’s Eighteen Acre café

.Tom Parker

The wineries are also more appealing to the big global players who want a presence here. From the humblest of beginnings, Bolney is now building a winery capable of producing 750,000 bottles a year, and last year Linter sold a controlling stake in the enterprise to Henkell Freixenet, the wine and spirits giant. From an initial plan to make 20,000 bottles each year, Ridgeview now has a new cellar capable of aging a million bottles at a time—and has declined buyout offers from the big Champagne houses, which are still very much in the market for English acquisitions.

If Bolney and Ridgeview typify the boot-strapping pioneers of English wine, then Sarah and Mark Driver exemplify another breed: the passionate investors. Stellar careers—Sarah as a lawyer, Mark co-managing the Horseman Capital hedge fund—enabled them to buy the 600-acre Rathfinny estate in a beautiful fold of Sussex’s South Downs hills. Before they’d planted the first of their 385,000 vines in 2012, Mark went back to school at Plumpton College to study viniculture, and when it was mentioned in class that the Rathfinny estate, formerly an arable farm, had been sold and would become a vineyard, he raised his hand and admitted that he’d bought it.

Rathfinny founders Sarah and Mark Driver

Tom Parker

Mark and Sarah revel in the details: the muselets, or wire cages that sit over the corks of their wines, are color-coded—pink for the rosé, black for the Blanc de Noirs—and if you undo them with your right hand, the Rathfinny crest set into the cork will be correctly oriented. That care is reflected in the wines they produce: Crisp, elegant and an easy equal to a Champagne, they’re sought out by top London hotels, including the Dorchester and the Berkeley.

The investment required to create a top-notch sparkling-wine enterprise from scratch is immense—not only in the land but in the planting, the buildings, the vast presses and tanks trucked over from Champagne, the hundreds of staff at harvest and the long wait for a return. The Drivers expect to break even for the first time this year, and I suggest to Mark that their personal investment in Rathfinny might not have met his professional criteria as a hedge-fund manager.

“It’s a generational investment,” he replies. “The old adage that you plant a vineyard for the next generation is true, because it takes you eight years from planting your first vine to selling your first bottle of wine. We wrote a 30-year business plan, and we’re about to write a hundred-year plan for the entire estate.”

“But there was some logic to it,” he adds. “We knew there would be strong domestic demand. And we also did an analysis of the climate. We have weather records here going back 120 years which show that average annual temperatures flatlined for a century until the 1980s and then started gradually increasing. Our average annual temperature is now one degree higher, and that, sadly, is what we’re benefiting from.”

If you’re thinking that now might be a good time to invest in English wine, you’d be right. There’s still plenty of desirable, south-facing, well-drained land not yet under vine. Although much of southern England shares the same chalk terroir as Champagne, Greg Dunn and other experts insist that it’s not required to make superlative sparkling wine, and many of the great English vineyards sit on different geologies. You’ll pay around $24,500 per acre, plus another $21,000 or so to put the vines in, according to Nick Watson, a land agent at Strutt & Parker who brokers such deals. That’s a fraction of what you’d pay for land in Champagne, with considerable upside should the current boom maintain momentum. But the land seldom comes onto the open market: You’ll have to approach the landowners through an agent such as Watson and negotiate an off-market sale. And you might find yourself bidding against one of the big Champagne houses.

Taittinger, founded in 1734, has now planted its own vineyard, Domaine Evremond, in Kent. The French brand insists that it’s simply a passion project, driven purely by the founding family’s respect for English wine and not by fears of falling Champagne sales in the UK or an existential risk to Champagne itself.

“We see the effect of global warming, but we’re not afraid,” says Christelle Rinville, Taittinger’s vineyard director. “Thirty years ago, harvest started at the end of September. Now it’s the beginning of September. But one of the strengths of Champagne is its ability to react. Even after the phylloxera epidemic in the 19th century, we were able to make great Champagne again. And maybe we’re in the same position again, at a crossroads, and that the future will be more difficult. So we have to think about our practices, our rootstocks and even our grape varieties and perhaps include those which can support hotter temperatures and less rain. But we’ll never lose sight of the need to maintain the character of Champagne.”

A starter of charred sea trout is served with focaccia baked with grapes from the vineyard at its restaurant, Tasting Room.

Tom Parker

“Champagne will always be Champagne,” she insists. “It’s internationally recognized, and it’s only a very small proportion of all the sparkling wine produced globally. English sparkling wine is very interesting, and very good, but it’s no different than the competition we face from other regions in the world.”

The 15 million bottles likely to be produced by the entire English wine industry this year are just a tiny fraction of the nearly 2 billion bottles the country consumes annually. The UK is the world’s second-largest importer of wine, after the US, and the biggest market for Champagne. The Brits have good taste, deep pockets and a natural affinity for home-grown products, so English sparkling wine can be scarce even in the UK as high-end restaurants and hotels (and the Royal Household) hoover up the best bottles. Central London alone could easily consume England’s entire wine production, and only around 5 percent makes it out of the country.

“We want scarcity,” says Mark Driver. “We want adventurous consumers, the people who love to discover new wines and then bring their discoveries to their friends.” If that’s you; if you’re bold enough to serve something other than Champagne to your guests and challenge them to tell the difference, you can find English sparkling wine in most major markets, but you’ll have to seek it out. King Charles III served Ridgeview at his first state banquet, held in honor of the president of South Africa. So you’ll be in good company when you celebrate with a bottle of Ridgeview or Rathfinny—even as you curse the changing climate that creates it.